Designing for Inclusion and Engagement in Microbiology Learning

As a microbiology student, I’ve seen how learning design can make or break whether concepts “stick.” Module 3 highlights that inclusive design is about anticipating learner variability, supporting belonging, and keeping students motivated. In science-heavy courses like microbiology, these ideas are essential. Students enter with different strengths: some excel in lab skills, others in theoretical understanding. Thoughtful learning design helps bridge these differences so that all learners can succeed.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

UDL is about designing courses that account for learner diversity from the very start, rather than fixing barriers after they appear. It emphasizes multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement ensuring students can access material, demonstrate understanding, and stay motivated in different ways.

Examples from Microbiology Learning

| UDL Principle | Example in Microbiology |

|---|---|

| Multiple means of representation | Using diagrams and videos to illustrate bacterial cell structures alongside written explanations |

| Multiple means of action and expression | Allowing students to submit lab reflections as written reports, oral presentations, or digital infographics |

| Multiple means of engagement | Using real-world case studies on antibiotic resistance to spark curiosity and relevance |

UDL reminds me that strategies designed for accessibility, like captions on microscopy videos, benefit everyone by reinforcing comprehension.

Inclusive Learning Design

Dr. Terence Brady’s TED Talk reframed how I think about inclusive education. He explains that Universal Design for Learning should function like architectural design built for access from the start rather than “retrofitted” later. This proactive approach ensures that education meets the needs of all learners, just as accessible buildings serve people of all abilities.

In microbiology, inclusion means anticipating variability and embedding flexibility into every stage of design. For example, scaffolding complex ideas like DNA replication through visuals and vocabulary support can help learners grasp molecular processes more effectively. As learners gain confidence, supports can be reduced to encourage independence.

Strategies educators can use include:

- Integrating culturally and globally relevant case studies (e.g., public health microbiology in different regions)

- Providing visual and linguistic scaffolds for complex concepts

- Gradually reducing supports to promote learner autonomy

Designing for Diverse Learners

There is no such thing as an “average” microbiology student. Each learner brings unique strengths and challenges, and instruction should balance high expectations with multiple pathways to success.

| Challenge | Support / Pathway |

|---|---|

| Strong in chemistry, weak in statistics | Scaffold microbial data analysis with guided tutorials |

| Strong in memorization, weak in application | Use open-ended case studies connecting pathways to real systems |

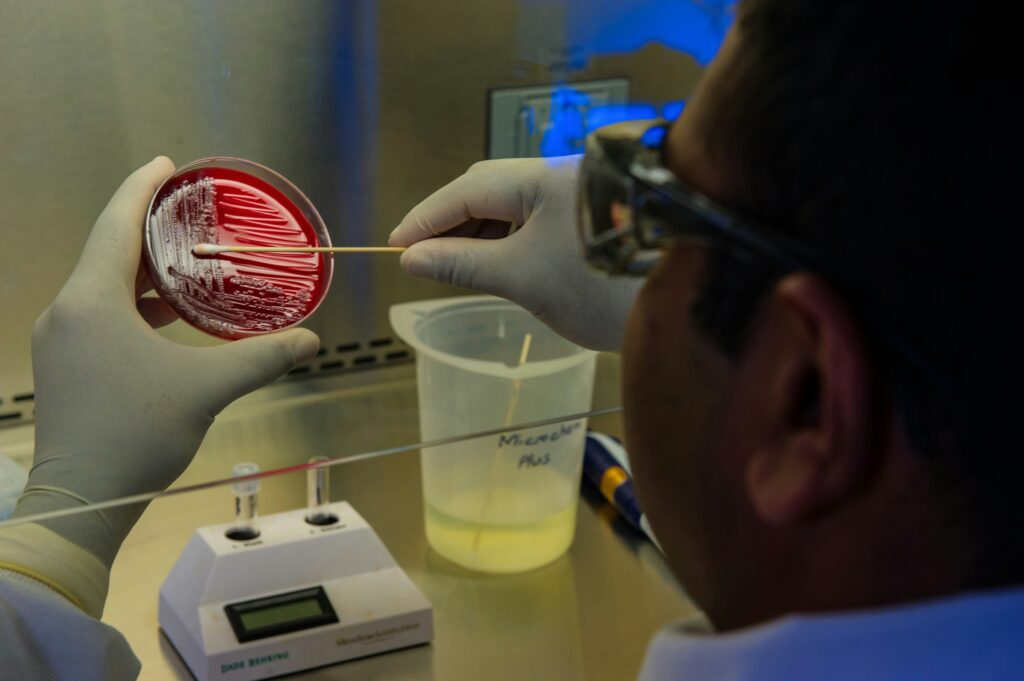

| Interested in theory, less confident in labs | Offer digital simulations and collaborative lab partnerships |

By embedding UDL principles into microbiology learning, educators can design with empathy and flexibility so that every student can thrive, whether they’re decoding metabolic pathways or troubleshooting a failed PCR.

Motivation and Engagement

Motivation shapes how deeply I learn. I’ve found I’m most engaged when learning feels meaningful and connected to real-world microbiology.

- Relevance: Studying microbial communities and their link to climate change made the content feel urgent and purposeful.

- Autonomy: Choosing my own lab report topic gave me ownership of the research process.

- Authentic tasks: Designing a mini-research proposal moved me from surface memorization to deeper application.

- Feedback: Timely and specific feedback clarified my growth and built accountability.

These elements echo constructive alignment, where activities, assessments, and outcomes work together to support both motivation and mastery.

Synchronous and Asynchronous Learning

Both modes serve valuable but different purposes in microbiology education.

| Mode | Strengths | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronous | Immediate feedback, peer interaction, real-time problem-solving | Lab sessions, Q&A, and experiment troubleshooting |

| Asynchronous | Flexibility, time for reflection, ability to review complex material | Recorded lectures on detailed processes like glycolysis |

Balance: Record live sessions for those unable to attend, build discussion boards for peer collaboration, and offer alternate paths to achieve learning outcomes regardless of schedule or location.

Principles of Effective Online Education

An effective online microbiology course should be:

- Aligned: Clear outcomes such as “Compare prokaryotic and eukaryotic gene regulation.”

- Accessible: Transcripts for lectures, alternative formats for dense data, and flexible submission options.

- Transparent: Weekly outlines connecting labs, readings, and assessments directly to learning outcomes.

Frameworks like UDL help maintain this alignment so that learning remains equitable and purposeful.

Interaction and Presence

Interaction builds engagement in online microbiology environments:

- Student–content: Virtual labs, microbial growth simulations

- Student–student: Group poster projects on microbial ecology

- Student–instructor: Personalized feedback and office hours

These create a sense of community that mirrors collaborative research spaces in real science.

Conclusion

Module 3 reinforced that inclusive design is as critical in microbiology as it is in any other discipline. Universal Design for Learning ensures barriers are minimized from the start, while inclusive design fosters equity, belonging, and motivation. Balancing synchronous and asynchronous modes supports flexibility, and thoughtful assessment design encourages deep learning. When educators combine theory with empathy and purposeful planning, they create microbiology learning environments where every student, regardless of background or ability has the tools and confidence to succeed.

References

Brady, T. (2017, February 10). Universal Design for Learning: A paradigm for maximum inclusion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRZWjCaXtQo